Midwestern summers are exceptional for their warm days and extended daylight and, encouragingly, this summer has also brought some relief to stock prices. Even when including some recent declines, the major indexes have gained ground since mid-June.

In August we marked 30 months of investing during the pandemic (since the prior peak in stock prices on February 19, 2020). In those 30 months, investors have faced two bear markets with a sizable gain sandwiched in between. During that time U.S. stocks, as measured by the S&P 500, have seen a cumulative gain of +22%, as of August 30, 2022. In contrast, an index of U.S. Treasuries declined by 7%. So much for the perceived safety of owning Treasuries in periods of weakness and higher volatility.

The biggest issue affecting markets now, and one which has had an arguably greater impact on the aforementioned bond market, is inflation. Never to be forgotten, inflation is a “tax,” due to the purchasing power it erodes. Moreover, as Milton Friedman stressed, inflation is a monetary event caused by excessive growth in money supply. Not to dismiss the pain that the pandemic has had on society, but inflation is like a virus as well, capable of wiping out our asset gains and household income growth.

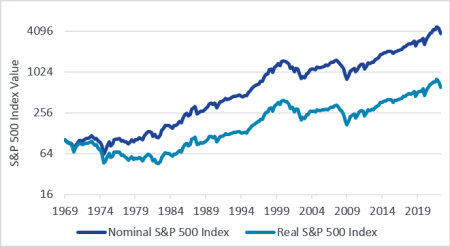

To illustrate inflation’s corrosive impact, the following S&P 500 Index chart includes both nominal and real (inflation-adjusted) values. Specifically, the years from 1969 to 1981 witnessed a prolonged decline in real stock prices, dropping 50% as the U.S. experienced an era in which the inflation rate averaged 6.5% and peaked at over 10%, well above its long-term average of 3% inflation.

S&P 500 Index Nominal vs. Real Returns

In a brief speech at a recent Economic Policy Symposium, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell emphasized that the current 8% inflation rate is unacceptable and that the Federal Reserve would need to continue to pursue restrictive monetary policy. This was the right message, though the current inflation rate has less to do with supply chain constraints or the war In Ukraine, in our opinion, and more to do with the era of low interest rates following the global financial crisis and more recently the rapid pickup in monetary stimulus that began in March 2020 and extended into this year. To be fair, the stimulus in the early days of the pandemic was the right policy, yet it simply went too far in providing that sugar buzz for the economy.

While in the very near term the capital markets have reacted negatively to Powell’s speech, this is the necessary monetary policy if we are to avoid a repeat of 1969-1981. Regarding portfolio values, we expect they will achieve more favorable returns in the long run if inflation is lower rather than higher. Generally, an inflation rate of 4% or less has produced better stock returns. In contrast, a rate of inflation trending higher and above 4%, has produced negative real returns.

Part of the reason we remain more optimistic about the current fight with inflation is that many publicly traded U.S. companies took advantage of previously low interest rates to finance or refinance their debt at longer maturity, fixed-rate debt. As a result, higher interest rates should have a more limited impact on profitability and potential stock price returns than in past periods when interest rates were rising due to inflation. That is largely the same for U.S. households that refinanced their personal debt, such as mortgages, at lower rates and presently have stronger balance sheets, resulting in stronger consumer free-cash-flows than in previous inflationary periods.

In summary, midwestern seasonality is a given and stock prices witness their own version of short-term seasonal changes. Nevertheless, in our years of managing portfolios, we believe that the merits of a low inflation economy, combined with the ability of high-quality businesses to innovate and create long-term value for their shareholders, can weather any near-term seasonality.